Guest sermon: Archbishop says....Most

of us are frustrated with the structures of the Church, and are feeling

that the way in which we do our business is, at the moment, preventing

us from doing what we actually want to do as a Church

posted by Peter Menkin, Obl Cam OSB

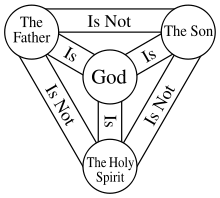

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

From

this morning’s gospel ‘And he could do no deed of power there’.

Frustration is one of the commonest of human experiences. Get two human

beings together in almost any circumstances and sooner or later they

will begin to talk to one another about what has frustrated them. And I

dare say that if you got any two members of General Synod together the

conversational material wouldn’t be that different.

So let us name

it this morning: many of us in the Church are feeling profoundly

frustrated. We’re feeling frustrated with each other of course, and

that’s more or less routine. That’s part of the shadow side of life in

the Body of Christ and the mysterious incapacity of other Christians to

see that we are right. Many of us are profoundly frustrated at the

bishops – and I shouldn’t wonder if some of the bishops weren’t as

profoundly frustrated with each other and with others in the Church.

Most

of us are frustrated with the structures of the Church, and are feeling

that the way in which we do our business is, at the moment, preventing

us from doing what we actually want to do as a Church. A lot of people

will be frustrated with the media and the way in which the Church’s

story is told in the media – and I know for a fact that the media are

very frustrated with the Church.

But when we’ve said all that

about the General Synod and the Church, we can look more widely and

remember that, to paraphrase the words of the prophet Isaiah, we are a

Church of frustrated hearts, dwelling in the midst of a people of

frustrated hearts, living in a society where frustration becomes more

and more acute and painful day by day. The frustration of people unsure

about the value of their pensions, the frustrations of graduates not

knowing if they will ever find steady employment, the frustration of

those not listened to, not attended to, the frustration of well meaning,

well intentioned people in public life trying desperately to solve

sixteen problems at once.

And this morning the Holy Spirit has

provided us with three readings about frustration. We begin with the

call of the prophet Ezekiel, a call not just to be a prophet, but to be

an extremely unsuccessful prophet. We forget that the prophetic call in

the Old Testament is not simply to be a blazing figure of admired public

integrity, it is to be a despised eccentric (no wonder Jonah ran away).

We hear about the frustrations of the apostle Paul, a frustration of

whatever it was that he called ‘the thorn in the flesh’, which prevented

him not only from making the impression that he wanted to make, but

still more frustratingly - and isn’t this the greatest frustration that

we can ever have – prevented him of thinking as well of himself as well

as he wanted to. We have the frustrations of the twelve foreseen by

Jesus in the gospel, those occasions when they seem to have no option

but to dust off their sandals and move on. And then most terrifyingly

and soberingly, we have the frustration of the incarnate word of God ‘He

could do no deed of power there’.

And those words bring to a head

all that we have been reflecting on, seriously and not so seriously,

because at the heart of it all lies one terrifying fact: there is no

power that can force the human heart. That is both the glory and the

bitter problem of our human condition. The glory of our human

condition: the dignity of freedom and conscience that God has bestowed

upon us. And the bitter problem of our human condition: because we

cannot force our neighbours to be with us any more than God can force

his creation to be with him. As we gather for worship we may very well

repent this fact of our human condition, and yet, at the same time,

remember to give thanks for it. This is the glory of our condition.

Our freedom, our dignity is God’s greatest gift and is what makes us

human. The possibility of frustration, in other words, is part of the

price we pay for being in the image of a God whose power is made perfect

in weakness.

How are we to respond? No power can force the human

heart. So how does the human heart change? It changes when it is broken

by love. It changes with the revelation that nothing is too costly to be

expended upon us. That is the nature of the love of Christ – that, and

that alone, is what breaks and remakes the human heart. That moment

when we recognise ourselves afresh and know our worth, our dignity, at a

completely new level. And somehow, if that is what changes the human

heart, that is what we seek and struggle to enact with each other. What

changes my neighbour’s heart? The recognition that nothing matters to me

more than my neighbour’s joy. That is how God changes the neighbourhood

of creation - and that is where we fail again and again. It is not

surprising that we fail, because what exactly that means in the

particular dilemmas and challenges of our life together, is not crystal

clear. How are we to love unconditionally without betraying what is most

real for us and in us? Issues of conscience that divide us are not idle

or arbitrary, they are about

that question. And yet, nagging

away again and again at all of us, is that basic truth – nothing will

change unless my neighbour knows that her or his joy is what, most

deeply, I care about. I have said it is where we fail - we make anxious

calculations, we mass defensively against each other, we try desperately

to find ways around love, and very often in the history of the

Christian Church we have cut that Gordian knot through schism. And we

live, it is worth remembering again, in a society where it doesn’t very

much look as though anyone’s joy is much in view, and where so many

people are profoundly convinced that the last thing in their neighbour’s

heart is the longing for their joy.

But to speak of joy

underlines the great risk that we run in all this. Frustration leads to

anger and indignation. And, of course, for well brought up Christians,

anger and indignation are normally internalised as depression. And the

last thing our society or our world needs is a depressed Church. That is

something which I trust we shall bear in mind and heart in the days

ahead.

So, where do we turn? We turn to St Paul who appealed to

the Lord about this: ‘But he said to me “My grace is sufficient for you

for power is made perfect in weakness”’. ‘

My grace is sufficient’

– one thing to hold onto, because frustration at least reacquaints us

with our humanity in its glory and its difficulty. And reacquaints us,

most importantly of all, with why exactly it is that we need the love of

Christ, and how it is true that we cannot ever love ourselves into

healing and into life. Instead of simply allowing our frustration to

turn inwards into anger and unhappiness, let us at least remember that

we are brought up against the reality of a humanity – rich, mysterious,

exciting, enduring and worth the very life of the Son of God himself. ‘

My grace is enough’.

But

one final thought on what from this morning’s scriptures we might lay

to heart: ‘He could do no deed of power there, except that he laid his

hands on a few sick people and cured them’. Just as inNazarethwe don’t,

it seems, very often let Christ do what he fully wants: the great work

of making us free, the great work of making us human, reconciled to his

Father and one another. But Christ passes on, I imagine, with a wry

smile at the people ofNazareth, like the wry smile he bestows on the

people of the Church of England and theChurchofGodmore widely. And he

acts anyway. Maybe we won’t let him do what he really wants, but Christ

– subtle and secret as ever – slips behind our defences and, just wryly

smiling, touches a few people into life, perhaps whispering to them

‘get on with it’. With that wry smile before us, perhaps we can remember

that we as a Church may yet be a place where he lays his hand and

heals. Whatever the frustration we feel with each other, however many

the ways in which we feel helplessly that we are stopping Christ and

ourselves from achieving his will, nonetheless he laid his hands on a

few sick people and cured them. Mysteriously he managed to get in touch

with those people who knew they needed healing, and he gave them what

they wanted.

I came across in reading this morning an image that I

have been struggling to fit into this sermon because it seemed to be

something that needed to be said, though why I’m not at all sure. It is

an image from a remark made by a Welsh farmer’s wife in a very poor area

of westWales, struggling to make ends meet. Asked how difficult it was

she shrugged, perhaps with another wry smile, and said: ‘Bread comes

down the chimney’. Our eucharist is perhaps a celebration of that bread

that comes down the chimney – that mysterious slipping behind our

defences that manages to feed us, frustrated and quarrelsome as we are,

and to make healing possible. But if he is to move on, to touch us, to

lay his hands and heal, we have at least to sit still - still enough to

let it happen.

© Rowan Williams 2012

.jpg)